Jaan Toomik’s solo exhibition, entitled “My End Is My Beginning. And My Beginning Is My End”, opened on February 13 and will be ongoing until March 24 at the Moscow Museum of Modern Art. The title of the show refers to a rondeau by the 14th-century French poet and composer Guillaume de Machaut, in which an entire musical composition is repeated, note by note, in reverse. The motif of recurrence is one of the established forms of inner organization in Toomik’s works, while the idea of the cyclical nature of life and its union with death are key themes in his art. Jaan Toomik is perhaps the most internationally known Estonian artist.

Toomik’s solo and group shows have been featured on such high-profile art platforms as Centre Georges Pompidou (Paris, 2012), MUMOK (Vienna, 2009), Galerie nationale du Jeu de Paume (Paris, 2000), Hamburger Bahnhof (Berlin, 1999-2000), the 22nd São Paulo Art Biennial (1994), Manifesta 1 (1996), the 47th and 50th Venice Biennales (1997; 2003), the 4th Berlin Biennale (2006), etc.

Jaan Toomik. Dancing with Father. Video still. 2003

The Moscow show consists of paintings, sculptures, short films and videos created by the artist in the past twenty years.

Many of Toomik’s videos are documentations of his happenings and performances, and they often bear a distinctively personal nature. For example, in one of his better known videos, “Dancing with Father” (2003), the artist is dancing on the grave of his late father to the music of Jimi Hendrix, where he is trying, according to the artist himself, “to establish a contact with him by overcoming an inner taboo”.

In his signature video, “Father and Son” (1998), he is meditatively skating across a vast icy field, naked, accompanied by religious chanting performed by his own son. The show will take the viewer through every stage of Toomik’s creative endeavors: from his fascination with neo-expressionism and postconceptual installations to performance and video art. We talked to Viktor Miziano, the curator of the show, who is also the editor of Moscow Art Magazine, an art theorist, and a frequent guest and participant of Latvian artistic projects, to find out why Toomik deserves such grand exposure to the Moscow public and how his works could be interpreted.

Jaan Toomik in front of a self-portrait in 2007. Photo: Marina Pushkar.

What was your first contact with Jaan Toomik – how did you meet?

It’s interesting to remember. It is difficult to pinpoint the moment we first met. It was probably the first Manifesta in 1996. I met him while he was mounting the show where he was presenting his work Dancing Home. Many more encounters followed, including those related to our mutual projects. Why does Jaan Toomik interest you as a curator?

To a degree, the post-Soviet, post-communist theme has been at the core of all my work as a curator. In this sense, I have never tried to reject my roots. On the contrary, I see it as my best resource in the international professional environment – it gives me energy and material, and determines my perception of the global situation from this very angle. Therefore, Jaan, as one of the brightest stars of the Baltic art scene, is obviously very appealing and understandable to me. As someone from Moscow and who has worked within the Moscow context, I have always had an interest in the artists from neighbouring countries who also touched upon the same topics that I followed and described in my immediate environment. Yet their approaches to these topics were often completely different. That is why I was interested in artists from, say, Central Asia, who have worked a lot with the social postSoviet experience, with the post-Soviet trauma, but did it in a completely different way. Jaan Toomik was a similar example: of course, his work, to a large degree, correlates with Moscow Actionism – with what Osmolovsky, Kulik, and Brener used to do. It is also Actionism, shamanism, a radical gesture, transgression. At the same time, it was all done with intonations, motivations, and imaginative solutions that were foreign to the Russian context. What is also curious is that a whole bunch of artists from the 1990s, with whom Toomik could be compared to, are now either doing something completely different or have gone into other spheres and are less active in art.

From this perspective, Jaan is unique because he remains a very active artist who is evolving and changing, and who has moved beyond what he used to do in the 1990s, when he was cultivating such clear, brutal and straightforward gestures.

Now Jaan works in incomparably more complex, sophisticated ways, and in different formats and genres; for example, he’s been passionate about artistic cinema. While all this is true, he nevertheless holds on to this impulse from the 1990s, which is something he used to share with many other Moscow artists.

Jaan Toomik. Waterfall. Video still. 1’45”, DVD, 2005

Don’t you think that in the case with the Russian Actionists, the question often is about a certain attack on the outside world – an intervention into it and its order, whereas Toomik’s radical gestures are directed onto himself, into his own inner world: memories, turmoils, losses...

You’re right; Russian artists don’t exhibit such a piercing existential note. Perhaps one can notice it in Aleksandr Brener, who created works relating to his father and works addressed to his wife. He did indeed have such “intimacy”, but Brener would later try to divert these themes away and into ideology – tie them with politics. He tried to embed this existential anguish into contemporary thematics of international (mostly Western) critical discourse. Osmolovsky, however, from the very beginning was a doctrinaire and a political artist. His radicalism directly appealed to Guy Debord and the tradition of the 1960s–early 1970s. Even if Toomik has it, it appears on a much smaller scale and in less programmatic forms. What is important for him is the element of dialogue with the world – the world as being, as a primal force, which in part brings him closer to Kulik. Kulik had worked with these issues on two or three occasions, which were the very issues that made him incredibly famous. But it was where he basically stopped, whereas Toomik was able to evolve, comprehend, variate, connect to different imagistic motifs and make them his own, which in a sense makes him a great authority on these topics and issues. In this sense, none of the Moscow artists can be compared to him. He built his own path, his own niche, his own problems, thereby creating for himself an absolutely unique place in it.

The post-Soviet experience is quite post-traumatic in its own way. In many of his works, one can trace an intention to deal with some sort of traumas, not necessarily social or global ones, but personal ones, which are perhaps, at the same time, reflections of these very global issues. Yes, yes, I absolutely agree. Especially given that the Baltics saw the political transformation of the 1980s–early 1990s as something very positive, as liberation and a return to the long-cherished independence. It is all very understandable. However, despite the fact that the social consciousness did not perceive this as trauma, what was crucial was the very experience of the breakdown of the order of things, the symbolic order which seemed unshakable, yet had disappeared in an instant. This experience shows how fragile any symbolic constructs are, any symbolic hierarchies and reference points – how they are unable to cover up a certain basic level that Agamben calls “the naked life”. As I see it, for Toomik, this familiarization with this basic level is very important. And this is what makes him extremely interesting: that among the artists of his generation, he was the most able to methodically, emotionally and dramatically embody its image.

A naked man on naked earth is a kind of reference point for existence, ontology and artistic expression – this is what can be called the key to reading this artist’s work. Toomik is known for working with very different media. Is this illustrated in the exposition? Was it built chronologically? No, no. We actually made it a point not to show his work chronologically, but as a certain compilation of motifs, key topics, a compilation of his artistic world. And it makes the show quite unusual because there can be two large video works next to his paintings, which, as we see it, reinforce each other. There are halls where several simultaneously playing videos “collide”, allowing the viewer to witness the dialogue.

In the case with “Father and Son”, which became the most popular of his works, we show it together with a video made nine year later and which has the same title. These works occupy one space but they are shown in turns because succession is important here. When one video stops, the other comes on.

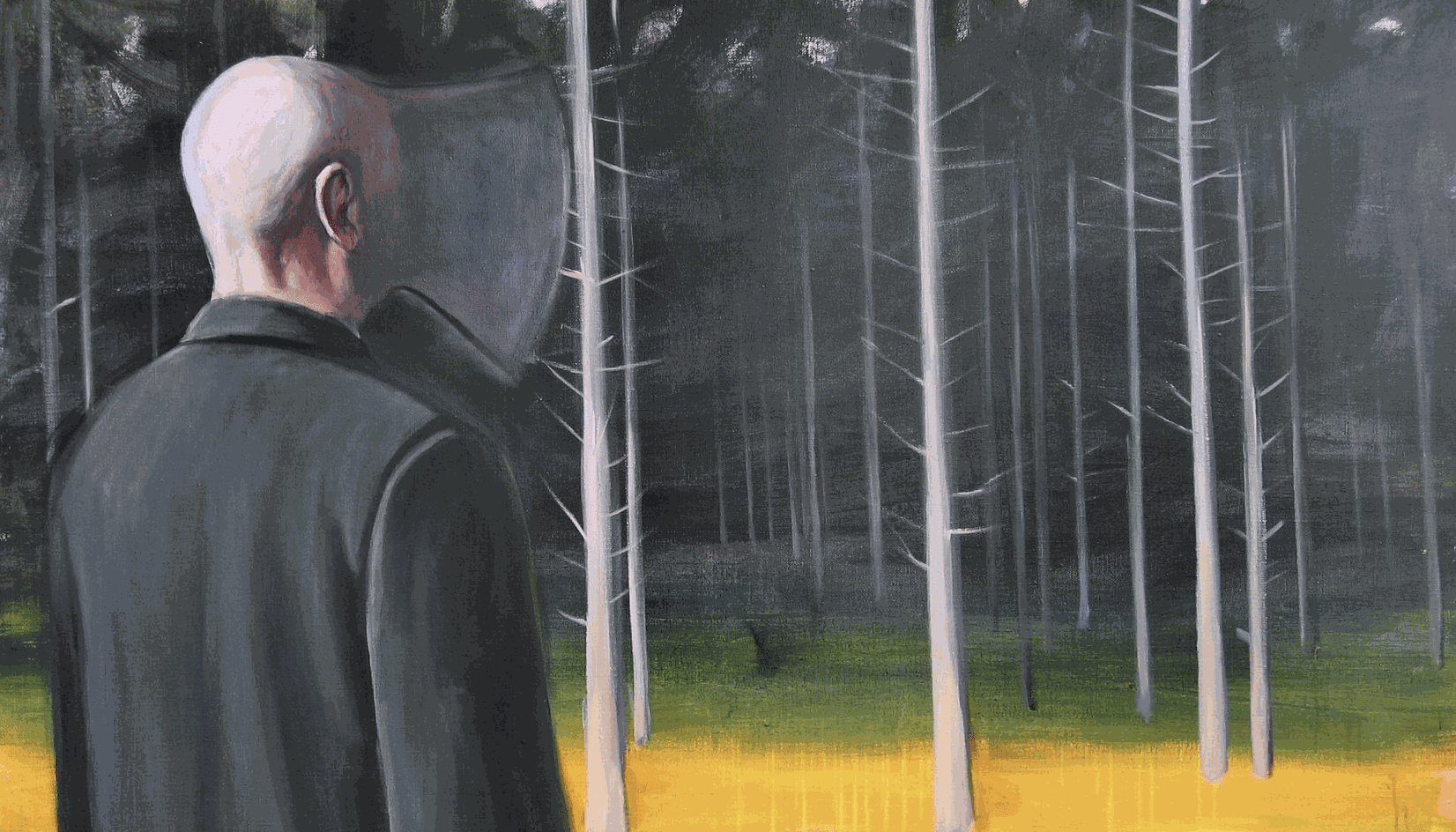

Jaan Toomik. In the Forest.2004